With the unveiling of the BBC micro:bit, the BBC is putting its name behind a new piece of electronics. But this is not the BBC's first such foray: over thirty years ago, at a time when few people had ever set eyes on such a thing, the BBC commissioned the development of a new personal computer. This is part one of a retrospective on that venerable icon of British technology, the BBC Micro.

A tale of two machines

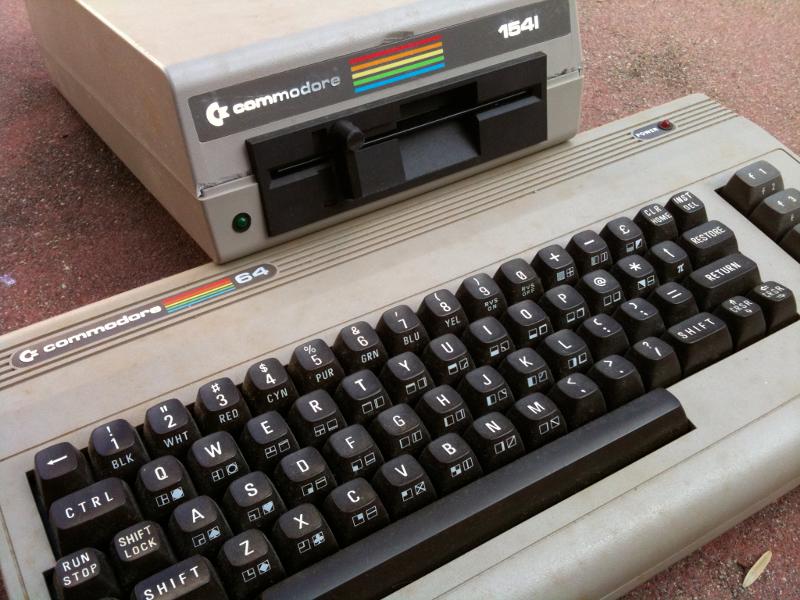

The early eighties were interesting years for home computing in the UK. The BBC Micro was released in late 1981, the ZX Spectrum a few months later, and the Commodore 64 made it across the pond by 1983, having been released in the US the previous August.

The Spectrum, the successor to the minimalist ZX81, retailed for £125 (with 16K of RAM) or £175 (with 48K). Less than half the cost of the £399 BBC model B, many corners were cut to reach that price point, such as the much-loathed rubber keyboard. (The men behind the Spectrum, Richard Altwasser and Steven Vickers, went on to create an even more minimalist machine, the Jupiter Ace. In a market eager for bigger and better, it sank without a trace.)

Instead the Beeb, as the BBC-branded machine was affectionately known, went head-to-head with the similarly-priced Commodore 64. They had much in common: they both consisted of a single unit with a full-travel keyboard, they both had an 8-bit 6502 CPU at their core, they both came with BASIC in ROM, they both plugged into a TV set (if you couldn't afford a monitor) and loaded programs from audio cassette (if you couldn't afford a disc drive), they were both widely used for games, and they both sold by the million.

But the difference in philosophy between the two machines was substantial, due in no small part to their respective manufacturers.

Commodore owned the chip fabrication company MOS, makers of the 6502. They designed a custom 6502 variant, the 6510, along with custom video and sound chips for their new machine, initially intended to be a games console. Acorn had no such resources: they had whatever they could buy off-the-shelf, and ingenuity.1 Instead their real expertise was software: they already had several years' experience writing code for the 6502, including a BASIC interpreter, the idiosyncratic Atom BASIC.

So Acorn's strategy in designing the BBC Micro was clear. Step 1: make the CPU run as fast as possible. Step 2: write good code.

Step 1 was achieved by the inclusion of newly-emerging 4MHz DRAM chips (Sophie Wilson relates how Acorn got their hands on the fewer-than-half-a-dozen chips that existed in the UK at the time). With memory clocked at 4MHz the CPU could run at 2MHz, accessing RAM every other cycle, while the video subsystem soaked up the remaining cycles. This allowed the Beeb to offer a full 80-column bitmapped screen—640×256 individually-addressable pixels—while running the CPU at full speed, a feat the much-more-expensive IBM PC achieved only by having a separate 16K of video RAM.2 For comparison, the Commodore 64 clocked its processor at just under 1MHz, and even at that speed some cycles were stolen for video.

Step 2 was just a Small Matter Of Programming. (“A lot of work... but we're used to that” —Sophie Wilson again.) Not so much a machine as a platform, the BBC Micro was the first microcomputer with a vision. An early step in a far-reaching design, abstraction was key: BASIC was logically distinct from the operating system, which offered an enormous API for programmers in all languages.

Arguably the Commodore 64 was the more capable machine, certainly for games, but the Beeb was vastly more useful out-of-the-box. While the C64 had powerful custom graphics and sound chips, they were largely invisible to new users. Its BASIC, licensed from Microsoft, was text only: it lacked any graphics commands, and was incapable of drawing even text when in anything other than the default character-based video mode. As for sound, it couldn't so much as beep without the user poking hardware registers.

The Beeb, on the other hand, offered a high-resolution graphics package in ROM, which included an exceptionally useful “filled triangle” operation. Triangles were useful on the Beeb for much the same reasons that they remain useful today as the hardware primitive for almost all 3D graphics. A documentary from 1983 shows some of the possibilities, as well as an example of the kind of television programmes the BBC produced having commissioned the machine.

Sound was equally well catered for, and in general the operating system exploited the hardware to the hilt. Combined with an excellent BASIC implementation, and befitting the niche it found in education, the Beeb was a computer for getting things done.

[1] The Beeb, like the Spectrum, had a custom video ULA (an early factory-programmable precursor to modern FPGAs). But it was essentially just a fast look-up table—what would now be called a RAMDAC—and nowhere near the complexity of Commodore's full custom ASIC designs.

[2] Sadly for PC users, the video RAM was slow to write to and wasn't dual-ported, leading to the infamous “CGA snow” effect.

Top Comments

-

shabaz

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

+3

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

-

Zad

in reply to shabaz

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Zad

in reply to shabaz

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children