Rice University researchers developed a new technique that transforms materials containing carbon into graphene. (Image Credit: Rice University)

Due to its excessive cost, ranging from $67,000 to $200,000 per ton, graphene isn’t widely used in everyday applications. Plus, the bulk production process is difficult. For instance, some techniques involve chemical vapor deposition or exfoliation to produce graphene. Rice University researchers recently developed a new process that rapidly converts coal, food waste, and plastic into graphene flakes at a cheaper cost compared to other graphene-producing techniques.

“This is a big deal,” James Tour, a Rice University chemist, said. “The world throws out 30 percent to 40 percent of all food because it goes bad, and plastic waste is of worldwide concern. We’ve already proven that any solid carbon-based matter, including mixed plastic waste and rubber tires, can be turned into graphene.”

The researchers say bulk graphene composites containing metals, plastic, plywood, concrete, and various building materials can be used for flash graphene. They are currently testing out graphene-enhanced concrete and plastic.

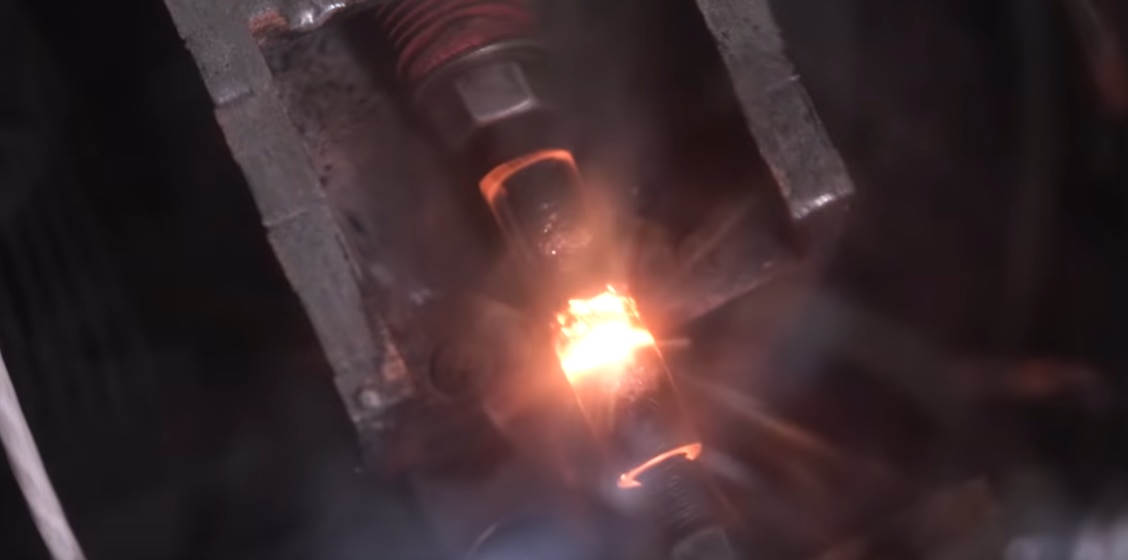

The team used flash Joule heating, a less costly and simpler technique that doesn’t require toxic solvents or chemical additives. Instead, a carbon-based material gets exposed to extremely high temperatures reaching 5000°F for ten milliseconds, causing chemical bonds to break apart. Non-carbon atoms are transformed into gas, which emits into the custom-designed reactor. The carbon then reforms into graphene flakes.

This technique also produces turbostratic graphene, whereas others produce A-B stacked graphene, where half the atoms in one graphene layer cover another graphene layer’s atoms. A tighter bond forms between these two sheets, which makes it more difficult to pull them apart. On the other hand, turbostratic graphene doesn’t have this quality, making it easier to separate.

A component in concrete is one potential application the researchers envision for these graphene flakes. “By strengthening concrete with graphene,” said Tour, “we could use less concrete for building, and it would cost less to manufacture and less to transport. Essentially, we’re trapping greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane that waste food would have emitted in landfills. We are converting those carbons into graphene and adding that graphene to concrete, thereby lowering the amount of carbon dioxide generated in concrete manufacture. It’s a win-win environmental scenario using graphene.”

A 0.1% concentration of flash graphene in cement that binds concrete could reduce its environmental impact by a third. Cement production releases 8% of human-made carbon dioxide per year.

In two years, the team wants to produce a kilogram a day of flash graphene, which would start with a project funded by the Department of Energy to convert US-sourced coal. “This could provide an outlet for coal in large scale by converting it inexpensively into a much-higher-value building material,” Tour said.

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell