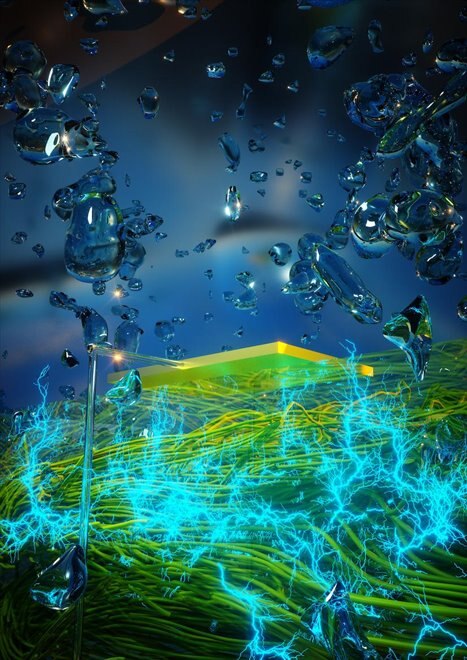

Artist’s drawing of the thin film device generating electricity with nanowires. (Image Credit: University of Massachusetts)

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have developed a device made from protein nanowires harvested from the microbe Geobacter sulfurreducens that generates electricity from moisture in the air. This new technology could have major implications for renewable energy, climate change, and medicine in the future. The team published their findings in the journal Nature on February 17, 2020.

“We are literally making electricity out of thin air. The Air-gen generates clean energy 24/7,” said Dr. Jun Yao, an electrical engineer at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “It’s the most amazing and exciting application of protein nanowires yet,” added Professor Derek Lovley, a microbiologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The air-powered generator is renewable, inexpensive and non-polluting. It can even be used in places with very low humidity to generate electricity, like the Sahara Desert. There are also some pretty significant advantages the device has over renewable energy, like solar and wind, since the air-powered generator doesn’t rely on sunlight or wind to function and it works indoors.

The device uses a thin film of protein nanowires measuring 7 microns thick. The bottom of the film is positioned on top of an electrode, while a smaller electrode that covers part of the nanowire film is placed on top. This type of exposure enables the film to absorb water vapor from the air. A combination of the electrical conductivity and surface chemistry of the protein nanowires, along with the pores between the nanowires in the film, creates the conditions that generate an electrical current between both electrodes.

The air-gen device is capable of powering small devices like smartphones and more. (Image Credit: University of Massachusetts)

Currently, the air-gen device generates a voltage of 0.5 volts, with a current density of 17 microamperes per square centimeter. This isn’t very much energy, but if multiple devices are connected, it could produce enough power to charge smartphones and other electronic devices. In the future, the team will develop a small Air-gen patch that could power wearable devices like smartwatches and health monitors. Doing so would eliminate their need for traditional batteries.

“The ultimate goal is to make large-scale systems. For example, the technology might be incorporated into wall paint that could help power your home. Or, we may develop stand-alone air-powered generators that supply electricity off the grid. Once we get to an industrial scale for wire production, I fully expect that we can make large systems that will make a major contribution to sustainable energy production.”, says Yao.

To continue producing the otherwise limited supply of protein nanowires, the team developed a microbial strain from E. coli. that could potentially mass-produce the nanowires “We turned E. coli into a protein nanowire factory,” Lovley says. “With this new scalable process, protein nanowire supply will no longer be a bottleneck to developing these applications.”

The creation of this new device was almost accidental when Xiaomeng Liu, a Ph.D. student in Yao’s lab, was experimenting with sensors and he noticed something unexpected happened. He stated, “I saw that when the nanowires were contacted with electrodes in a specific way, the devices generated a current. I found that that exposure to atmospheric humidity was essential and that protein nanowires adsorbed water, producing a voltage gradient across the device.”

Have a story tip? Message me at: cabe(at)element14(dot)com

-

dubbie

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

dubbie

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children