Artist's concept of a lightsail propelled by a laser and blasting off through space. (Image Credit: Credit: Breakthrough Starshot / Breakthrough Initiatives)

The Breakthrough Starshot Initiative isn't a new concept. Introduced by Stephen Hawking and Yuri Milner in 2016, it involves beaming lasers at probes attached to ultrathin sails, enabling them to reach extremely high speeds. By doing so, those sails can travel through interstellar space, eventually reaching Alpha Centauri.

Caltech has made some progress toward making this a reality. The team recently built a test platform to distinguish the ultrathin membranes that make the lightsails. With this platform, laser exertion force on the sails can be measured. It also allows the spacecraft to travel through space at extremely high speeds. Their tests are the first phase toward observations and measurements of crucial concepts and potential materials.

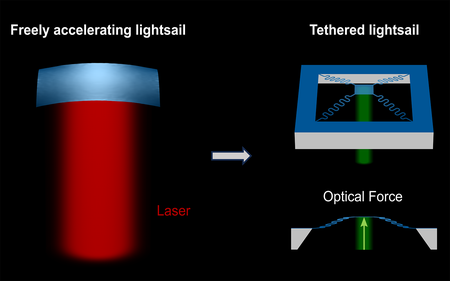

The researchers also aim to characterize the behavior of a freely moving sail. To investigate materials and the propulsive forces, they developed a small lightsail tethered to the corners of a larger membrane.

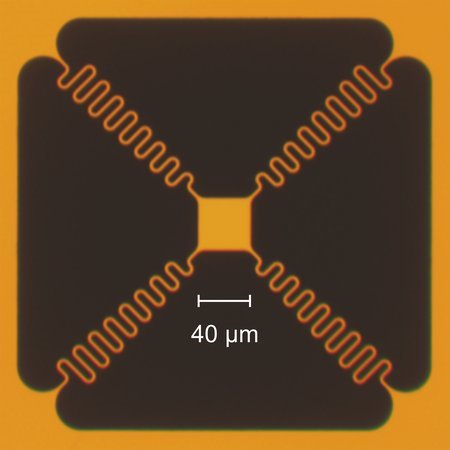

Microscopic image of CalTech's tiny lightsail tethered at the corners for measuring radiation pressure. (Image Credit: CalTech)

They used ejection beam lithography to produce a silicon nitride membrane pattern measuring 50 nanometers thick. The result is a trampoline-like membrane measuring 40 microns wide and 40 microns long. It uses silicon nitride springs at the corners to hold it in place. Afterward, the researchers beamed argon laser light at the membrane. This allowed them to measure radiation pressure impacting the tiny lightsail by measuring the trampoline's motions while it moved up and down.

However, the physics changes if the sail is tethered. "In this case, the dynamics become quite complex," says co-lead author Michaeli. When light hits the sail, it starts vibrating—much like a mechanical resonator. These vibrations occur due to the laser's heat and hide the radiation pressure's effect. The team saw this as an advantage for the light sail. "We not only avoided the unwanted heating effects but also used what we learned about the device's behavior to create a new way to measure light's force," explained postdoctoral scholar in applied physics Lior Michaeli.

The team's tethered lightsaid measures direct radiation pressure. (Image Credit: CalTech)

With this new technique, the device behaves like a power meter that measures the laser beam's power and force. "The device represents a small lightsail, but a big part of our work was devising and realizing a scheme to precisely measure motion induced by long-range optical forces," says co-lead author Ramon Gao.

So, the researchers developed a common-path interferometer that detects motion via the interference of two lasers. One beam hits the vibrating sample while the other traces a rigid area. Because those beams follow a nearly identical path, they pick up the same environmental noise, like equipment operating or people talking nearby. This cancels out the signal, leaving only the tiny signal from the sample's motion.

The team added the interferometer into the microscope to observe the mini sail and encased the device within a custom-made vacuum chamber. This allowed them to measure the sail's motions as small as picometers and the mechanical stiffness, which determines how much the springs deformed as the laser's radiation pressure pushed the sail.

They also tested how a sail responds when it's misaligned with the laser source. By angling the laser, they simulated this effect and measured the force on the mini sail. Then, they calibrated their results based on the device's laser power readings, allowing them to adjust for the beam spreading and missing samples of the sail. According to the paper, the team theorizes that the angled beam hits the sail's edge, causing parts of the light to scatter and move in various directions.

In the future, the team aims to use nanoscience and metamaterials for better control of the side-to-side motion and rotation of a mini lightsail. "The goal then would be to see if we can use these nanostructured surfaces to, for example, impart a restoring force or torque to a lightsail," says Gao. "If a lightsail were to move or rotate out of the laser beam, we would like it to move or rotate back on its own."

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell