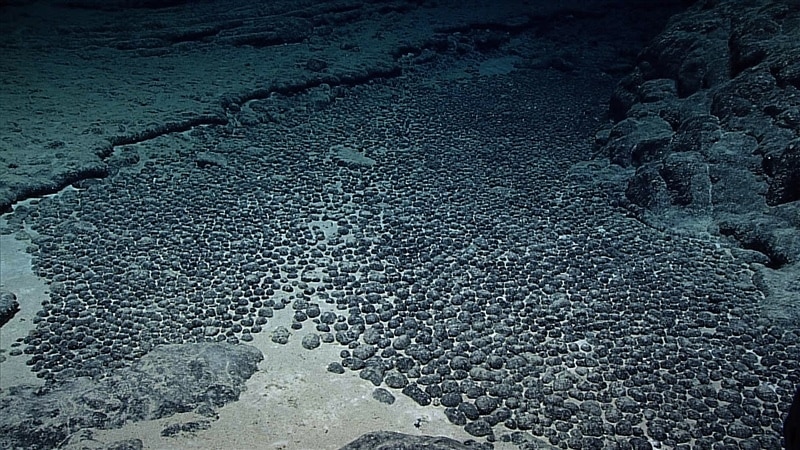

Image shows a field of manganese nodules in the Pacific Ocean. (Image Credit: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana)

I thought deep sea mining was the salvation the world’s resources need. I was very glowie writing the last post. Now, not so much…

Over a century ago, thousands of Americans eagerly dug around for gold during the gold rush era to quickly become rich. Some were successful in their hunt, while others failed. Now, a similar gold rush hunt could begin on the Pacific Ocean's seabed. Rather than gold, however, miners are going after rare-Earth minerals that power electric cars and other machines.

The UN-affiliated organization managing this new industry provided licenses for companies exploring the area even though full-scale mining didn't start. This could change quite soon since Nauru, a small Pacific island, evoked a two-year rule for the International Seabed Authority to set regulations to govern the industry.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean contains trillions of potato-sized manganese nodules on the seabed. Global rules for industrial-scale deep-sea mining still need to be set, however. Mining companies hope that these rules will be put in place by July 2023. Although these nodules were first discovered in 1875, underwater robotic developments recently made it possible to mine them on a large scale.

However, environmental campaigners warn against seabed mining due to the effects harming the ecosystems that are not yet fully understood. Estimates say that 90% of the species encountered in the deep sea by scientists have not been observed before.

Economic advisor on oceans for the Commonwealth Secretariat Daniel Wilde expected the ISA to provide a payment regime for mining companies that would receive a 17.5% tax profit. He also suggested that the two-year deadline seems rather close, and further questions could pop up without an agreement.

Aker BP's geologist Ebbe Hartz says that mining for seabed metals could replace oil drilling sometime in the future. However, finding the metals remains an issue, which requires sufficient data. Hartz suggests that machine-learning data collection could pave the way toward successful seabed mining. Doing so also prevents errors that usually occur with hydrocarbons.

Eleanor Martin, a partner at Norton Rose Fullbright, says global banks showed interest in deep-sea mining investment projects due to expected increases in lithium and cobalt costs. These minerals are essential for electric car batteries. However, the public still needs to be won over before companies begin mining the oceans.

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell