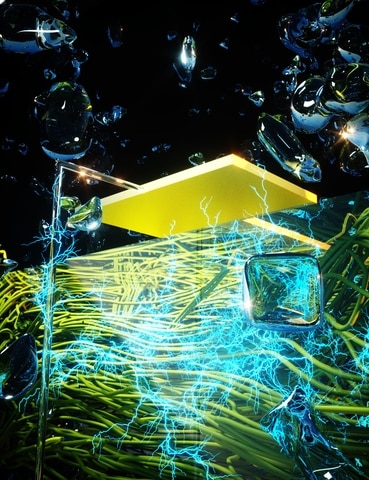

The team's Air-gen device pulls moisture from the air to generate electricity that can power devices. (Image Credit: Derek Lovley/Ella Maru Studio)

The University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers created an electricity-generating cloud by collecting moisture from the surrounding air. The team achieved this feat with their Air-gen device made of two electrodes and any material that has extremely tiny nanopores.

"This is very exciting," Xiaomeng Liu, lead author of the paper, said. "We are opening up a wide door for harvesting clean electricity from thin air." The pores are essentially small enough (100nm) that the molecule's electrical charge can pass through them and be harvested to generate electricity. This is the same process as clouds producing electricity in the form of lightning bolts.

Water molecules typically move through 100nm before they bump into one another. Molecules passing through a thin material with those tiny nanoholes cause a charge to build up in the material's top portion. Fewer molecules on the lower layer lead to a charge imbalance replicating the same effect within a cloud. Afterward, the electrodes send the electricity to anything that requires power.

This Air-gen device can operate at all times despite the weather conditions because moisture is constantly in the air. It generally relies on the air being full of electricity, which is difficult to harvest from lightning bolts. So they reproduced the effect found in nature.

"The air contains an enormous amount of electricity," says Jun Yao, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering in the College of Engineering at UMass Amherst and the paper's senior author. "Think of a cloud, which is nothing more than a mass of water droplets. Each of those droplets contains a charge, and when conditions are right, the cloud can produce a lightning bolt—but we don't know how to reliably capture electricity from lightning. What we've done is to create a human-built, small-scale cloud that produces electricity for us predictably and continuously so that we can harvest it."

In a previous study, the team developed a device with a bacteria-derived protein that uses moisture in the air to produce electricity. They soon understood that any material with very small holes could achieve the same thing. Such materials could be made of "a broad range of inorganic, organic, and biological materials."

"The ability to generate electricity from the air—what we then called the 'Air-gen effect'—turns out to be generic: literally any kind of material can harvest electricity from air, as long as it has a certain property," Yao said.

Even better, researchers can stack thousands of these materials to produce kW of energy. The team believes they can further develop these Air-gen devices to power wearables or even a house. However, they need to do this so it won't take up much space and can harvest electricity over a large surface area. "The idea is simple," says Yao, "but it's never been discovered before, and it opens all kinds of possibilities." The harvester could be designed from literally all kinds of material, offering broad choices for cost-effective and environment-adaptable fabrications. "You could image harvesters made of one kind of material for rainforest environments, and another for more arid regions."

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell