Artist’s rendering of a lanthanide-doped nanoparticle in the shape of a spider and the web (made of 9-ACA). (Image Credit: Zhongzheng Yu/)

Engineers at the University of Cambridge have developed a technique that enables the electrical activation of insulating materials by delivering energy indirectly rather than injecting charge. The team used this approach to develop low-voltage electroluminescent devices based on lanthanide-doped insulating nanoparticles. They achieved this by attaching organic molecules that act as energy-harvesting antennas. This approach has the potential to enable new near-infrared biomedical imaging technologies and high-speed optical data transmission.

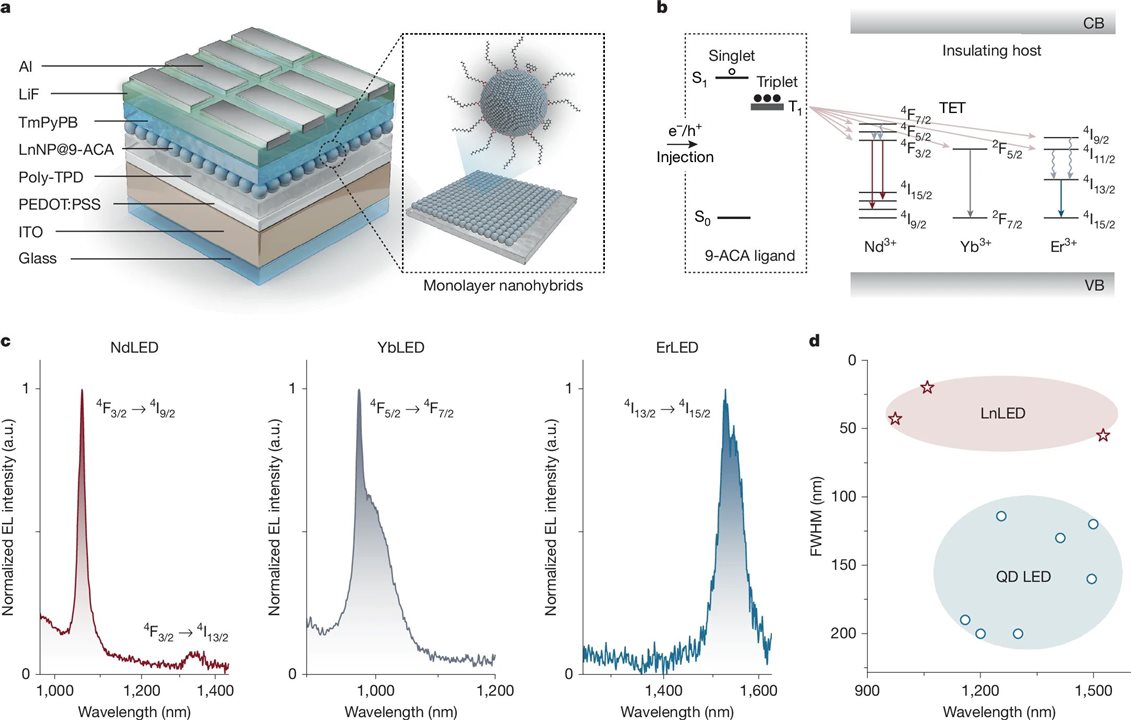

Lanthanide-doped nanoparticles produce very sharp, stable light emission that spans the near-infrared II (NIR-II) range from 1000 to 1700 nm. However, they are also challenging to drive electrically. Charge-carrier injection into the nanoparticle lattice has proven difficult at typical voltages because the materials are wide-bandgap insulators with energy gaps on the order of approximately 8 eV. Typically, optical pumping with lasers excites most lanthanide nanoparticles, making them less suitable for use in compact devices such as LEDs.

The team introduced a triplet energy transfer (TET) pathway to overcome this limitation. This method electrically couples organic molecules to insulating lanthanide nanoparticles. It functionalizes roughly 6 nm NaGdF₄:Nd/Yb/Er nanoparticles doped with lanthanide ions like Nd3+, Yb3+, or Er3+ by partially replacing insulating oleic acid ligands with 9-anthracenecarboxylic acid (9-ACA). 9-ACA has two crucial roles: accepting injected electrical charges and it has a triplet-excited state energy that matches the excited state of lanthanide ions.

Schematic diagram of the LnLEDs. (Image Credit: Nature)

Applying a voltage injects electrons and holes into the organic layer rather than into the nanoparticle. Recombination of 9-ACA molecules produces excitons, with approximately 75% being triplet excitons due to spin statistics. Triplet excitons persist longer, typically hundreds of microseconds, whereas singlet excitons decay within nanoseconds. This longer lifetime enables more efficient triplet energy transfer via a Dexter-type exchange mechanism that requires close proximity and orbital overlap between the organic molecule and the lanthanide ions at the nanoparticle surface.

Energy transfers nonradiatively from the 9-ACA triplet state to the 4f excited states of the lanthanide ions. The lanthanide ions then relax radiatively, generating their narrowband emission. Devices emit electroluminescence peaks at specific wavelengths, depending on the dopant. For example, Yb3+ emits around 976 nm, Nd3+ around 1058 nm, and Er3+ at 1533 nm. They achieved this emission at turn-on voltages around 5 V, significantly below the voltage required for direct electrical excitation of the insulating nanoparticles.

The team integrated these hybrid emitters into multi-layer LED structures and measured external quantum efficiencies over 0.6% in the NIR-II region after device optimization. This also includes using core-shell nanoparticle structures to suppress surface quenching. Such efficiency is very high for electrically driven lanthanide nanoparticle systems and suggests that TET serves as the dominant excitation mechanism.

This technique has the potential to lead to electrically driven near-infrared light sources in biomedical imaging, sensing, and optical communications.

Have a story tip? Message me here at element14.