Astronauts installed the ICARUS system on the International Space Station. (Image Credit: ESA/NASA/AstroSerena)

Bio-logging, also known as wildlife monitoring, has been around for a while and recently made some significant advancements. Back in the 1990s, researchers monitored mammals with devices as large as lantern batteries. Although technology has progressed, collars and tags are still quite large for three-quarters of the wild animals on Earth. Now, a project called the internet of animals allows scientists to monitor wildlife as they roam, migrate, and move around the planet. Two Russian astronauts successfully installed the system on the space station in August 2018, along with a large antenna and other equipment. It also provides detailed data on the world’s health.

Scientific teams began spreading out around the world to capture thousands of animals, such as blackbirds in France, fruit bats in Zambia, and rhinos in South Africa. Afterward, they outfitted lightweight and energy-efficient transmitters onto these creatures. Collected data then gets streamed into a project known as the International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space (ICARUS), which costs tens of millions of dollars.

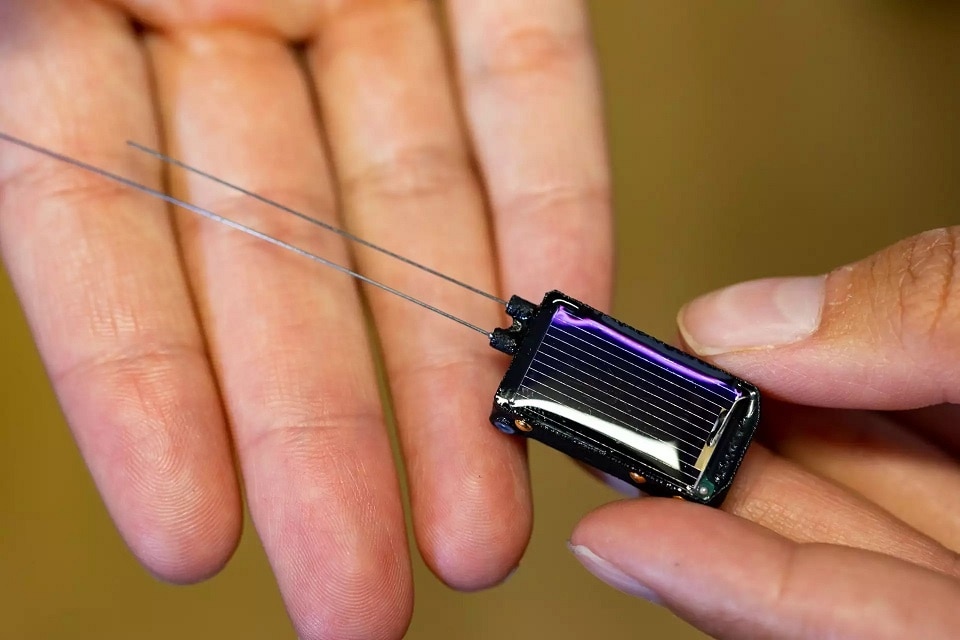

The 5-gram transmitter can monitor an animals’ migration, environment, and physiology. (Image Credit: MPI f. Animal Behavior/ MaxCine)

Each tracking device collects data on the animal’s position, physiology, and microclimate. That data then gets sent to the International Space Station, which transmits it back to computers on Earth. From there, scientists can track an animal’s movement as it roams on the planet, an advancement that was unimagined at first. Plus, people around the globe can monitor their favorite animals through a smartphone app.

ICARUS also completed various projects with some ongoing. The project is tracking young bears in Russia, Romania, the USA, and Canada to determine how they cope after being released back into the wild. Large mammals in Kenya also wear these transmitters to help researchers understand when poachers are moving. Researchers monitor blackbirds and thrushes in Germany, North America, Russia, and Tibet to understand where they live and how to protect them. Additionally, they want to understand the birds’ decision-making when it comes to migratory flight based on living in polar, temperate, or Mediterranean regions. The project can even keep an eye on bats, pangolins, and other animals playing roles in viral epidemics.

Attaching the transmitter is a cruelty-free, easy process that takes a few minutes and involves different techniques. For example, researchers use a silicon harness with elasticized straps for birds, allowing it to fit snugly on the body even while the bird gains or loses weight. Plus, the feathers easily hide the harness, so it’s difficult to notice at first glance. All these features ensure that the transmitter cannot affect the bird’s behavior and livelihood.

Songbirds, as shown above, can wear the ICARUS transmitter to monitor how they make decisions and migrate. Seems kind of big. (Image Credit: MPI f. Animal Behavior/ MaxCine)

In some cases, researchers collect blood, hair, or feather samples from the animals. Also, each animal wears a bird ring for tagging purposes to help characterize a bird and transmitter. Afterward, the team releases the birds into the wild, where they carry on with their natural activities. Transmitters can then collect and send data.

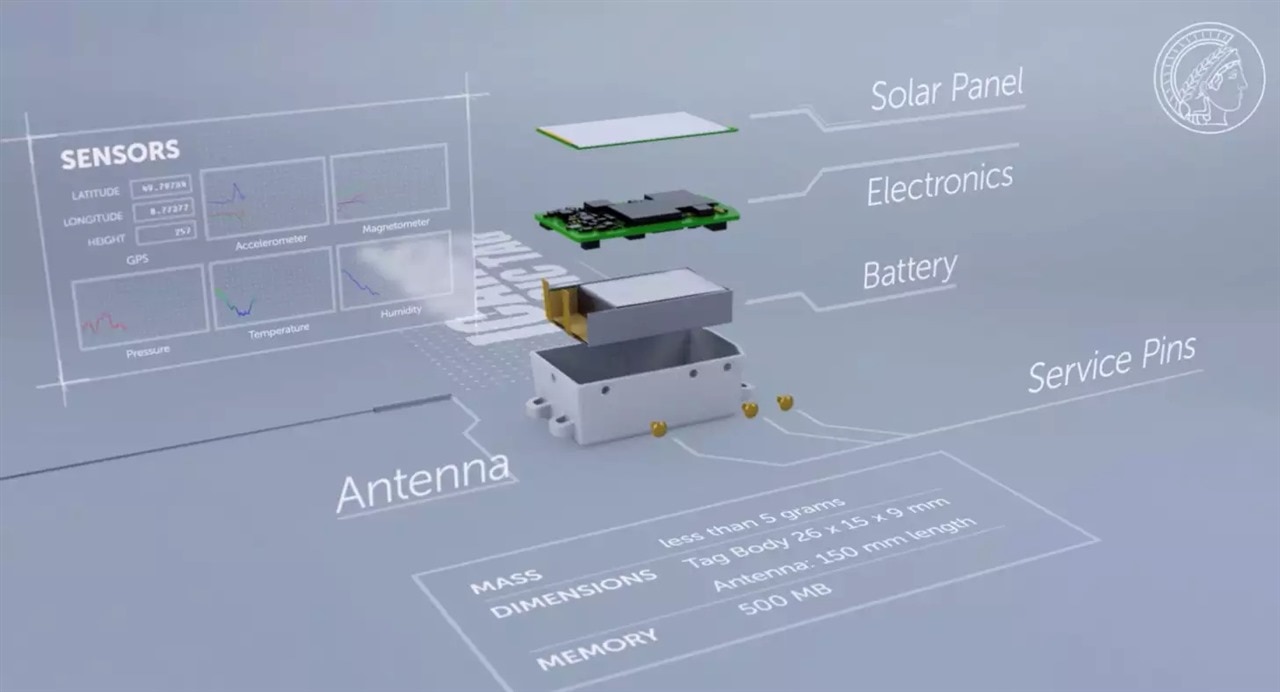

Each transmitter weighs just 5 g, housing a lithium-ion battery, a basic module to control the transmitter’s functions, and an application-specific radio module. It also contains an accelerometer, magnetometer, temperature, humidity, and pressure sensors, along with a GPS module, which calculates an animal’s location to a few meters. Onboard solar panels recharge the battery so it can distribute power for measurement purposes and data transfers. Two antennas are mounted on a transmitter as well. One measures 200mm for radio transmission, while the other measures 50mm for the GPS receiver. A memory chip is also integrated into each ICARUS tag, storing up to 500 megabytes of data.

The transmitter features a lithium-ion battery, solar panels, two antennas, a GPS module, and sensors to operate. (Image Credit: MPI f. Animal Behavior/ MaxCine)

As a whole, these devices consume very little energy and can last as long as the animal’s lifetime. The transmitter mostly operates in the standby mode because both the GPS and radio-transmitted signal consume most of the energy. This is momentarily interrupted to record and store data in the sensors.

This technology continues to serve a significant role in wildlife monitoring. However, sensors weighing five grams are too heavy for small animals, so they cannot be equipped with them. 70% of bird species and 65% of mammal species, along with amphibians or insects, cannot wear the sensors. So by 2025, the ICARUS team hopes to develop transmitters weighing just one gram, light enough for insects and smaller birds to carry. For now, the current ICARUS transmitter is ideal for other small animals, including fruit bats, parrots, baby turtles, and songbirds.

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell