(Image credit: Unsplash)

Electronic designs have become increasingly complex over the decades. A single device can combine high-speed digital interfaces, mixed-signal control loops, RF connectivity, and power electronics, all packed into a tight form factor. As systems have grown more integrated, the tools engineers use to debug and validate them have had to evolve as well. Modern oscilloscopes and analyzers are no longer just instruments for viewing waveforms; they’ve become platforms for understanding entire systems.

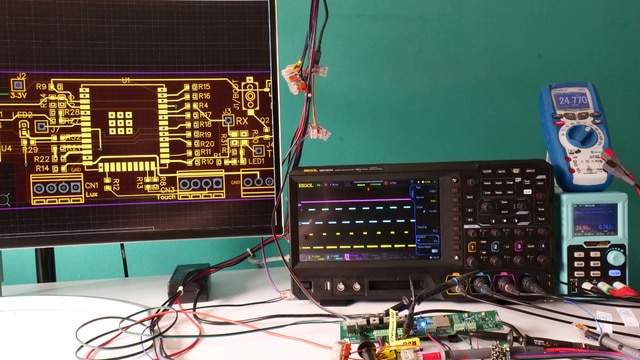

A typical oscilloscope’s job is simple: show voltage versus time. That still matters, but it’s no longer enough. Faster edge rates, denser buses, and software-defined behavior mean engineers need deeper visibility into what’s happening across longer time spans and multiple domains. Tech companies have responded with higher sample rates, deeper memory, and acquisition modes that capture rare or intermittent events without forcing engineers to read through massive datasets. This shift has turned oscilloscopes into tools for correlation, not just observation.

Spectrum and signal analyzers have also had to adapt to designs in which RF is no longer confined to a single subsystem. Wireless standards continue to push bandwidth higher, while coexistence and EMI concerns make it critical to understand how signals behave in the frequency domain. Real-time spectrum analysis has become increasingly important, especially for capturing short-lived or burst signals that swept analyzers can miss. Engineers working on RF designs now expect analyzers to reveal transient behavior that directly affects real-world performance.

As embedded systems have grown more complex, the line between analog and digital has blurred. Mixed-signal oscilloscopes reflect that reality by letting engineers observe analog waveforms alongside digital logic and decoded protocol traffic. Instead of treating buses like I2C, SPI, CAN, or USB as abstract bitstreams, modern scopes provide human-readable insight and align them directly with voltage behavior.

Power has also become a key measurement concern rather than an afterthought. With switching regulators everywhere and efficiency targets getting tighter, many of today’s oscilloscopes include power-focused analysis tools. Engineers can measure switching losses, inrush current, and transient response directly, without resorting to external math or post-processing. This makes them ideal for applications ranging from industrial automation to electric vehicles, where power behavior directly affects reliability and thermal performance.

Digital design has also pushed measurement requirements even further. Interfaces such as DDR memory, PCIe, and USB require increased bandwidth, low noise floors, and precise timing analysis. Modern oscilloscopes support eye-diagram analysis, jitter measurement, and signal-integrity tools that were previously available only on specialized equipment. These capabilities allow engineers to validate compliance and margins early, before problems surface during system integration or certification testing.

Capturing the right event remains one of the hardest parts of debugging, and triggering has become far more sophisticated as a result. Engineers can now trigger on protocol conditions, specific data patterns, runt pulses, or even frequency-domain behavior. Instead of watching a signal scroll endlessly, the instrument waits for something to happen. This reduces guesswork and shortens debug cycles, especially when issues only appear under specific operating conditions.

Beyond raw measurement capability, usability and workflow integration have become increasingly important. Many instruments now support remote control, scripting, and automation using familiar environments such as Python, enabling measurements to fit into automated test setups or regression workflows. As teams become more distributed, remote access and data sharing are no longer nice-to-have features; they’re part of the development phase.

Looking ahead, oscilloscopes and analyzers are continuing to converge toward software-defined platforms. Firmware updates unlock new analysis features, higher performance modes, and application-specific tools without requiring new hardware. There’s also growing interest in using machine learning to help identify anomalies and patterns in large datasets, including those for long captures or complex systems. Whether those features become mainstream or remain niche, the direction is clear: measurement tools are becoming smarter, more flexible, and more tightly integrated into the design process.

Have a story tip? Message me here at element14.