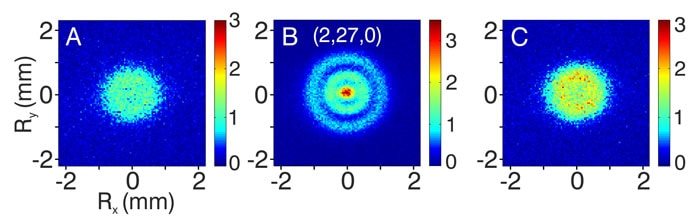

These images demonstrate on-resonance tunneling ionization through the Coulomb potential, with non-resonant ionization shown in A) and C). Meanwhile, B) shows resonant ionization producing a two-node wave function pattern. (Image Credit: Stodolna et al. Phys. Rev. Lett)

In 2013, researchers at the FOM Institute for Atomic and Molecular Physics (AMOLF) in Amsterdam captured the first visualization of a hydrogen atom’s electron orbital. The experiment involved using photoionization microscopy to convert abstract probability densities into observable interference patterns.

The hydrogen-orbital imaging used photoionization microscopy. This technique maps the spatial structure of an electron’s quantum wave-function via post-ionization interference analysis (nodal patterns in Stark states). The team used a tunable laser to excite hydrogen atoms from ground to highly excited (Rydberg) states. Rydberg states have large principal quantum numbers (n up to 25) that greatly expand the electron’s orbital radius from angstroms to micrometers. This amplifies nodal features, such as 0-3 rings, and scales sub-nm quantum effects to observable interference fringes through electrostatic magnification. As a result, the enlargement increases the electron’s nodal structure spatial scale. That also makes the interference behavior experimentally accessible with a lab-sized apparatus, rather than on sub-nanometer scales.

After excitation, the researchers beamed another laser pulse, which photoionized the electron. Once freed by the ionizing laser, the electron entered a carefully calibrated static electric field (approximately 1–100 V/cm), generated by parallel-plate electrodes in a vacuum chamber, acting as an electrostatic lens. The field then pushed the electron wavelength toward a position-sensitive detector while its wave function evolved with the field geometry, producing interference patterns from semiclassical trajectories. Those patterns map one-to-one with the original Rydberg state’s transverse probability distribution, revealing its nodal structure.

The detection system featured a microchannel plate (MCP) coupled to a phosphor screen and a high-resolution CCD camera. An electron produced a burst of light on the phosphor upon impact, which the camera captured. Collecting millions of these ionization events allowed the team to develop a statistically robust 2D projection of the electron’s interference fringes. They then compared this distribution with numerical solutions to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation under the same field conditions. Agreements between theory and experiment verified that the observed interference map encoded the nodal structure of the hydrogen electron’s orbital.

Have a story tip? Message me here at element14.