Loggerhead sea turtles were the subject behind the team’s project. (Image Credit: pixabay)

I like the idea of researching and protecting the planet. Not chasing the next big technological thing, but preserving what we have. In the process, honoring and truly loving life.

University of Oxford researchers developed a small, low-cost turtle tracking system called SnapperGPS that relies on satellite navigation and consumes little power. In summer 2021, the team placed it on endangered nesting loggerhead sea turtles in Cape Verde.

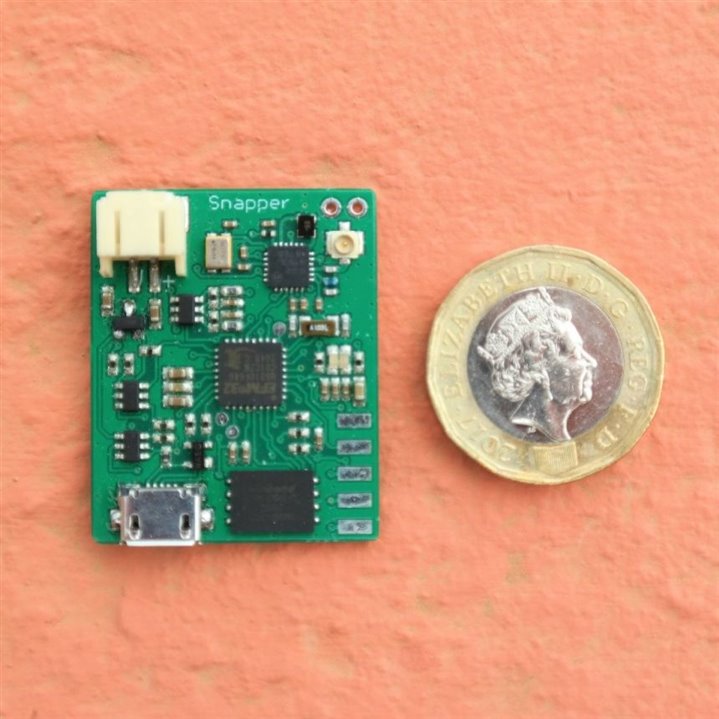

Overall, the team had one goal: making the hardware energy-efficient by performing minimal signal acquisition and processing. To achieve this, the researchers produced a web service capable of processing the signals in the cloud. As a result, they were able to create a bare-bone receiver for under $30 that can operate for over ten years on a coin cell.

They deployed a concept called snapshot GNSS, which only takes a few milliseconds for the signal to reach the receiver. However, SnapperGPS records those signals at a lower resolution compared to existing receivers. To solve this problem, the researchers developed and integrated three alternative algorithms to perform location estimation from short low-quality satellite signal snapshots, all of which are based on probabilistic models.

The team used the low-cost, low-power SnapperGPS system to monitor turtle activity. (Image Credit: University of Oxford)

Although navigation satellite signals can’t move through water, sea turtles often reach the surface for air. These short opportunities aren’t ideal for standard GPS methods to locate the receiver. Even then, a snapshot technique only needs a few milliseconds for the signal, making it suitable for marine applications.

Loggerhead sea turtles spend most of their time in the ocean, but mature females nest on the beach once every two to three years. They lay several batches of eggs every two weeks during their beach visit, making it possible to collect the hardware and captured data.

The team implemented the SnapperGPS tags in custom-made casings, which are waterproof to at least 100m. However, they were forced to deploy the tags during the late nesting season due to the pandemic. Doing so negatively affected the recovery rate since most turtles laid their last nest as they were tagged.

The researchers only recovered nine tags out of the deployed twenty. Some unexpectedly malfunctioned while the others recorded several location tracks showing odd behavior among turtles. The data offers newfound insights into Maio’s loggerhead sea turtle population. Additionally, the project taught the team important lessons that involved the difficult task of deploying SnapperGPS on a sea turtle. Now, the team is in the process of improving the system for the next season.

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell