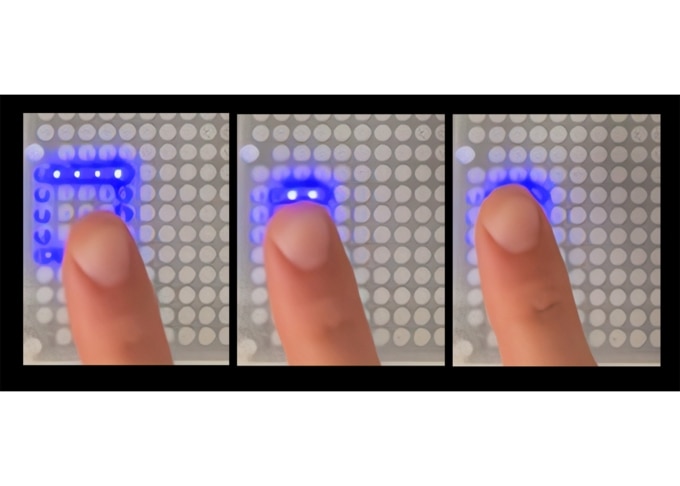

Researchers developed a screen patterned with tiny pixels that expand outward, forming bumps when illuminated, allowing users to see and feel the animations. (Image Credit: UC Santa Barbara)

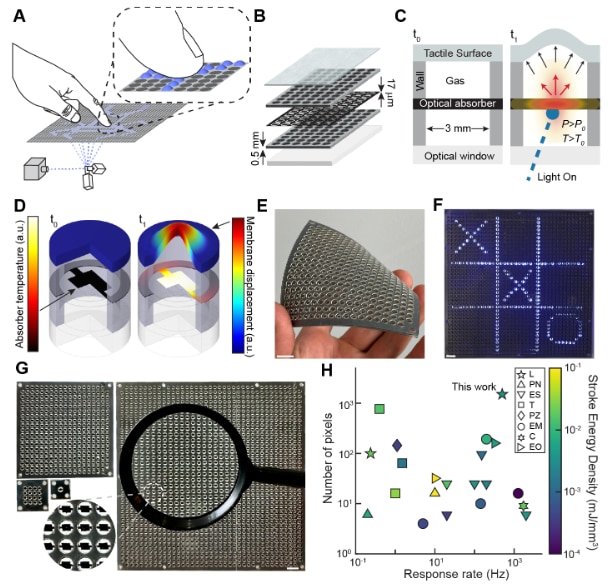

Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, developed a new type of tactile display. This system features a thin optotactile surface driven by an external scanning laser or projector, enabling users to perceive what they see through touch.

The system utilizes thousands of optotactile pixels, each featuring a small, sealed gas-filled cavity, a light-absorbing layer, and a thin, elastic membrane. When a projected beam of light hits a pixel, the absorbing layer heats up, gas expands, and a membrane bulges outward. This reaction produces a touchable bump on the display.

This technique is unique as the light powers and controls individual pixels, which means the system doesn’t require embedded motors or wiring under the surface. It’s challenging to scale modern tactile systems as a single pixel requires an actuator and electronics. With this design, the surface is completely passive since light provides the energy and behavior of the system.

The scalable tactile display converts projected light into visible and touchable patterns using arrays of optotactile pixels. (Image Credit: arXiv)

It also performs extremely well. Each pixel sufficiently moves to be perceptible by human touch. They also respond quickly, so that dynamic patterns and moving tactile features can be generated. The team developed displays consisting of 1,511 independently addressable pixels, exceeding earlier prototypes. Based on perceptual tests, users felt and tracked tactile shapes across the surface, demonstrating that it works as a fully functional tactile interface.

Due to the lack of mechanical components and wiring, the system can easily be scaled and adapted. Software instantly changes the patterns, enabling an individual surface to display different tactile experiences, depending on the visual content. The system has a variety of potential applications, including advanced human-machine interfaces, accessible interfaces for visually impaired users, touchscreens with real pressable buttons, VR and AR systems with true haptic feedback, and educational tools.

According to the researchers, the technology still needs work before mass production. Particularly, the system must be more energy efficient as each tactile pixel is active via localized heating driven by projected light. Improving the light’s absorption and mechanical motion conversion efficiency would reduce how much energy it consumes, while making larger displays more practical. They also need to enhance durability as the optotactile pixels use the elastic membranes and sealed-gas cavities that must withstand repeated deformation over time. Ensuring these structures can operate reliably over long periods without leakage or fatigue is crucial for real-world applications.

Have a story tip? Message me here at element14.