Water gliders are often deployed underwater to help study a hurricane. (Image Credit: University of Georgia Skidaway Institute of Oceanography)

Weather robots like torpedo-shaped watercraft gliders created by the University of Georgia’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography submerge in waters beneath hurricanes to gather data for accurate forecasts. These submersibles adjust their buoyancy and center of gravity to maneuver underwater in a zig-zag and up/down pattern. They feature air and water temperature sensors that collect water temperature and salinity data while moving.

Researchers then rely on this temperature data to figure out the heat availability that leaks into the atmosphere, feeding a hurricane or any tropical activity. On the other hand, the salinity data gives them an idea as to how much some of that energy transfer might be capped. Once they collect the necessary data, the gliders remerge every 4 – 6 hours, transmitting results to help forecast models.

Most of these submersibles work with NOAA’s sail drones, vehicles designed to float atop the ocean surface to study hurricanes. This means both vehicles are collecting data from above and below the ocean surface while a storm hits. With the sail drone, researchers can determine how much heat goes back and forth between the ocean and the atmosphere. Other instruments are also onboard, measuring solar irradiance, barometric pressure, air temperature, humidity, wind, waves, water temperature, salinity, chlorophyll, dissolved oxygen, and ocean currents.

However, gliders don’t move as fast as other hurricane hunters, so they can’t act in rapid response. For that reason, the gliders weren’t deployed to study Hurricane Lee. Instead, the team intends to use the glider for monitoring important ocean features. Doing so gives them better insight into how storms rapidly intensify or the rapid intensification of a storm while losing some energy. So far, gliders are put to use along the eastern coastline from Florida up to Canada. The team hopes to deploy more in the future.

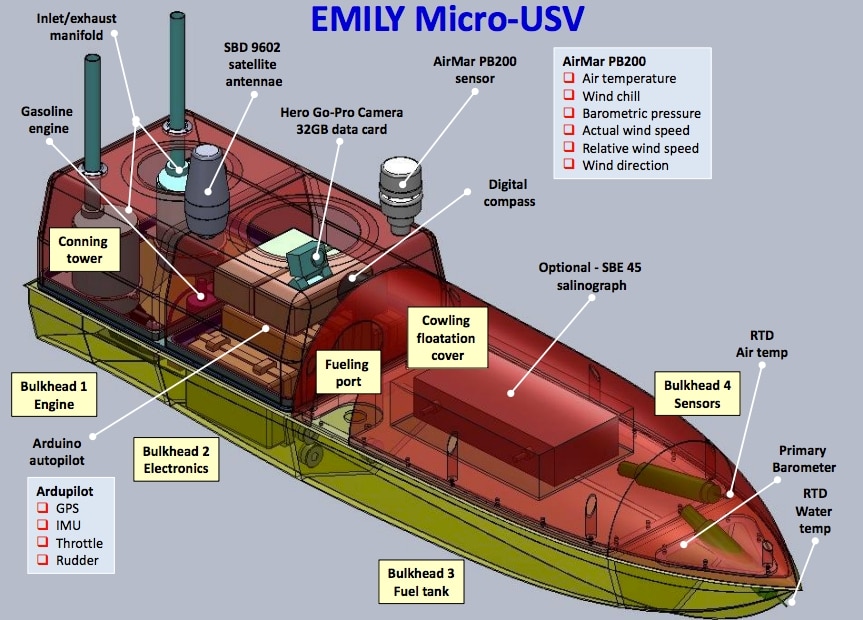

The modified EMILY vessel can track the eye of a hurricane. (Image Credit: NOAA)

NOAA’s re-engineered EMILY robot tracks the eye of a hurricane, making up for what the Wave Gliders cannot monitor. It has a gas-powered engine, a large fuel tank, and a battery. It’s still similar to the Gliders because EMILY also features air and water temperature sensors, barometric pressure indicators, wind speed sensors, a camera, and more. EMILY is often deployed ahead of an approaching storm and reaches its center, staying in place while streaming data as it passes.

EMILY focuses more on obtaining data about the pressure of the storm’s eyewall, which has thunderheads encircling the storm’s eye. A larger storm’s eyewall moves in cycles, which help determine whether or not a hurricane is gaining or losing strength.

NASA’s Global Hawk drone drops canisters into a storm from above to collect data on humidity, temperature, pressure, and more. (Image Credit: NASA Photo / Lauren Hughes)

In 2016, NOAA began using a Global Hawk military-grade drone for storm tracking. It has a 26-hour flight time, enabling it to travel from NASA’s facility on the Virginia coast to Africa’s west coast. Global Hawk even has an airborne vertical atmospheric profiling system that drops canisters into a storm, collecting humidity, temperature, pressure, and other data. An NOAA worker stationed thousands of kilometers away can instruct the drone to drop the canisters just by clicking a mouse button.

The drone also features other instruments that generate real-time wind and precipitation 3D maps. Compared to other techniques, this has resulted in more accurate storm information while it develops.

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell