Adding iron nanoparticles to the ocean’s surface could help plankton growth. (Image Credit: Pexels/pixabay)

Climate experts say that significantly reducing the number of greenhouse gasses that escape into the atmosphere must be achieved to prevent the worst climate change effects. However, doing that isn’t sufficient. Capturing the carbon present in the atmosphere would also go a long way. Tiny CO2-absorbing marine plants could help mitigate that issue.

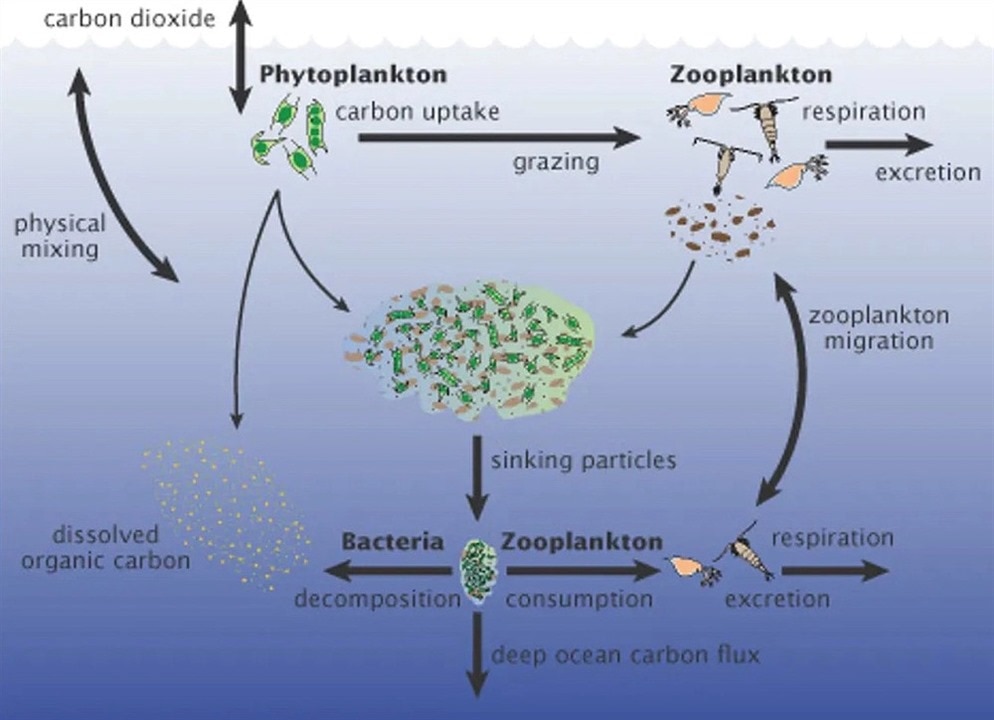

That can be done by taking advantage of the phytoplankton that thrives near the ocean’s surface, absorbing sunlight and carbon dioxide to generate energy through photosynthesis. After the phytoplankton dies off, some of that carbon sinks into the deep ocean. However, phytoplankton also needs iron, which isn’t widely available in some areas of the ocean, to grow. So if we supplement the oceans with more iron, then phytoplankton can thrive. For example, iron-rich volcanic ash that landed on the ocean surface caused phytoplankton to grow big enough that even satellites could detect it.

With that in mind, John Martin, an oceanographer, formed the iron hypothesis, which points out that filling the ocean with iron potentially produces more phytoplankton to help cool down the Earth. “Give me a half tanker of iron, and I will give you an ice age,” he said in a 1988 lecture. In 1993, Martin’s Moss Landing Marine Laboratories colleagues added more iron over 64 km2 of the Pacific Ocean, resulting in twice the biomass. “All biological indicators confirmed an increased rate of phytoplankton production in response to the addition of iron,” his colleagues wrote. Since then, other teams have performed various ocean fertilization experiments. And although they produced more plankton, it’s still a mystery if this technique can help in the fight against climate change.

Some carbon from phytoplankton ends up in the deep ocean. (Image Credit: NASA/A New Wave of Ocean Science/US JGOFS)

In 2009, the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory researchers monitored an ocean iron fertilization experiment in the Southern Ocean. They measured carbon particles 800 meters below the water’s surface and were discouraged by the results. “Just adding iron to the ocean hasn’t been demonstrated as a good plan for storing atmospheric carbon,” researcher Jim Bishop said. “What counts is the carbon that reaches the deep sea, and a lot of the carbon tied up in plankton blooms appears not to sink very fast or very far.”

In November, researchers noted that the fertilizer delivery process might make the idea work. Rather than supplementing the surface with iron sulfate, they suggest engineering iron nanoparticles that have properties to prevent problems that keep ocean fertilization from succeeding. Coating the nanoparticles in polymers would help them stay closer to the surface, boosting phytoplankton uptake. Providing them with light-absorbing properties for improved sunlight absorption could assist with photosynthesis.

“Our study shows that the use of several types of engineered nanoparticles in ocean fertilization can be promising in terms of costs and carbon dioxide emissions during production and delivery processes,” researcher Peyman Babakhani said.

However, adding iron nanoparticles to fight off the climate crisis would be a massive task, and further research is required to determine how it could affect ocean ecosystems. “Large-scale fertilization could have unintended and difficult-to-predict impacts not only locally, but also at great distances in space and time,” Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative researchers said.

Have a story tip? Message me at: http://twitter.com/Cabe_Atwell